In Myanmar's Buddhist culture, when it comes to making donations between monks and nuns, nuns have always been left behind - a deeply rooted practice in Myanmar's religious landscape. But that's not all.

Unlike monks, nuns cannot accept ready-made meals as alms. They also have fewer opportunities to give sermons, participate in religious events and ceremonies, or receive invitations to social functions like wedding ceremonies and house-warming celebrations. Even during the Buddhist Lent season, the tradition of offering robes (Kathein) is primarily centered around monasteries.

In Myanmar's conservative society, no one makes a big deal about nuns being treated as second-class members of the Buddhist order. It's not considered an issue worth discussing openly. Even when some people do speak out, they receive little support in the traditionally minded community, with criticism being more common than support. So how do these nuns survive in these challenging times?

What is a Buddhist Nun?

While the term "Thila Shin" (Buddhist nun) began to be used during the Konbaung Dynasty, the existence of nuns predates this period. According to Buddhist history, female monks (Bhikkhuni) first appeared in 585 BC, five years after the Buddha's enlightenment. When the Bhikkhuni order disappeared, they were succeeded by ascetics known as "Thithintha," who could be considered the predecessors of today's nuns.

During the Konbaung Dynasty, nuns didn't wear the pink robes seen today. They wore white cloth. This practice continued until King Thibaw's reign, and they were known as "Mae Thu Taw" (Lady Ascetics). During King Mindon's reign, as religious affairs gained more prominence, more women took up the nunhood. King Mindon himself encouraged his daughters to become nuns. Princess Pinhtein San of King Mindon and Queen Supayalat of King Thibaw were disciples of the famous nun Mae Khin.

Mae Khin was the sister of the renowned Shankalaykwin Sayadaw, known for her literary exchanges with the Banmaw Sayadaw. During King Mindon's era, she gained prominence as a teacher to princesses and court ladies, earning the title "Sayagyin" (Great Teacher). Mae Khin received her ordination from Sayadaw Htutkaung, leading to the saying "Nuns begin with Htutkaung" or "Nuns begin with Mae Khin." She spent her final days practicing meditation on Sagaing Hill, making Sagaing the birthplace of nun monasteries.

During that era, nuns would go for alms rounds like monks, following novice monks with their alms bowls. Their residences were called "Zayat" (rest houses).

In the late Konbaung period, the term "Thila Thin Sayalay" became popular, eventually evolving into today's "Sayalay" (nun).

Despite reaching the royal court, nuns never received the same level of reverence or material support as monks. Unlike men who could enter monkhood at their discretion, women faced restrictions. While society encouraged men to become monks, they were less supportive of women becoming lifelong nuns. Many biographical accounts of senior nuns tell stories of having to run away from home to ordain due to parental opposition.

Today, women can choose to become nuns based on their own will.

Contemporary Nuns

In present-day Myanmar, there are neither Bhikkhunis nor white-robed nuns remaining. When people think of nuns in Myanmar, they picture the pink-robed religious practitioners.

Unlike Bhikkhunis with their numerous precepts, or monks with their extensive Vinaya rules, nuns observe more precepts than lay people but are considered religious descendants rather than full clergy members.

Nuns make up about one-tenth of Myanmar's monastic population, approximately 60,000 in number. Until 1961, there were fewer than 10,000 nuns. It took 50 years to reach today's numbers.

Contemporary nuns face similar challenges as their predecessors. In Buddhist culture, a nun still doesn't receive the same respect or privileges as a monk. Since nuns don't receive formal ordination like monks, they don't enjoy the same religious or social rights.

The only significant change has been in their attire. Today's nuns have been wearing pink robes for over 100 years. This change occurred around 1900 when nuns visiting the Mahagandhayon Sayadaw in Sagaing were told their white robes looked too similar to lay people's clothes. At that time, nuns wore red-dyed lower garments and white tops. Gradually, white disappeared, replaced by today's pink.

Dana (Alms) Collection

Collecting alms has become almost synonymous with nunhood in Myanmar. Nuns and alms collection go hand in hand.

However, in the early Konbaung period, only monks could go on alms rounds. There's no clear historical record of when nuns transitioned to collecting uncooked rice instead. This transition became one of their fundamental challenges.

Nuns collect uncooked rice four days a month, two days before the full moon and new moon days. They must go door-to-door regardless of sun or rain. Besides rice, they sometimes receive small monetary donations, though this isn't always reliable.

After the familiar phrase "Dana San Pa Shin" (Please donate rice), responses vary from actual donations to apologetic replies like "Kan Taw San Pa Baya" (I pay respects but have no rice) or "A Khway Ma Shi Tay Lo Pa Baya" (I don't have any spare change yet).

This makes nuns' survival heavily dependent on these alms rounds. Moreover, people tend to believe that donating to monks brings greater merit, leading to a preference for preparing meals for monks while giving uncooked rice to nuns only when convenient or when they have excess.

Consequently, nuns' wellbeing becomes directly linked to public economic conditions. When people struggle financially, nuns struggle too. The public's economic situation directly affects nuns' ability to collect alms.

Living Quarters

There's a telling phrase about nuns' living conditions: "Nuns have no common dwelling." Compared to monasteries, nunneries are notably impoverished, and their numbers are significantly fewer.

Very few nuns can live independently in their own monasteries and focus solely on meditation, whether through personal wealth, donor support, or family assistance. Most nuns stay in monasteries or meditation centers, performing various duties in exchange for accommodation. They must collect alms, cook the rice they receive, and offer it back to their host monastery's senior monk.

Some live collectively in separate compounds, but this requires approval from the Ministry of Religious Affairs to construct buildings.

Establishing independent nunneries comes with its own challenges. Being women, nuns have additional needs, from menstrual supplies to daily necessities. This requires regular financial support, funding for education, and long-term sustainability through dedicated donors.

While new facilities like Theri Taw Village have emerged since late 2010, they aren't accessible to all nuns.

It's like the mythical king's dream of filling already-full pots - while impoverished nunneries continue desperately seeking donors.

Guardians of the Vulnerable

Despite their own frugal existence, nuns often maintain a maternal instinct that leads them to care for orphaned children.

Particularly, young girls from unstable ethnic regions are often entrusted to nunneries by their parents for education and safety. Some arrive as young as three years old.

The Saddhamma Manju Nunnery School in Thanlyin cares for hundreds of Palaung girls. These girls don the nun's robes and study from primary through high school levels.

Like these well-known, well-funded nunnery schools, smaller independent nunneries also provide childcare within their means. While they may not offer higher education, they ensure basic literacy and provide safety.

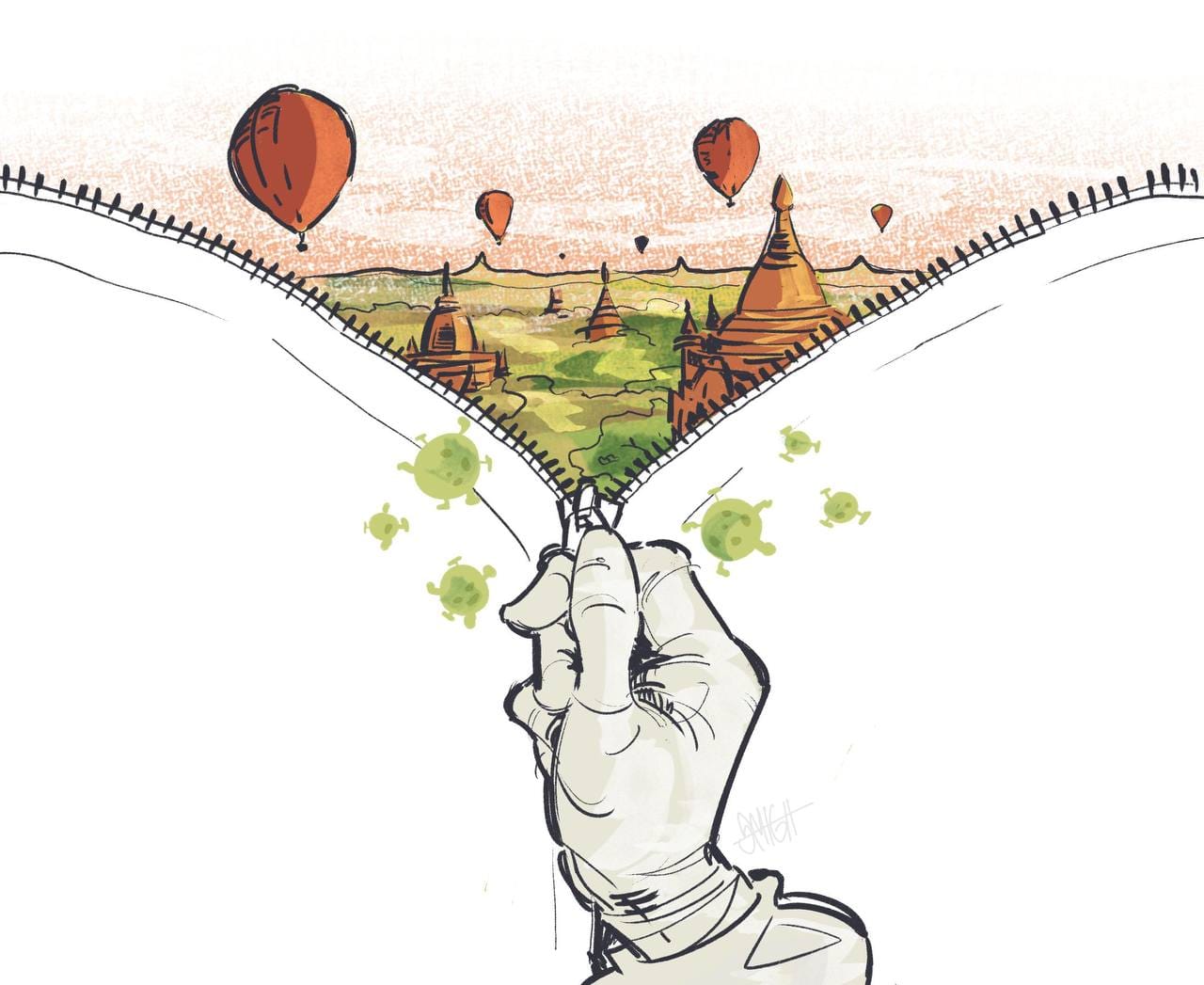

COVID, Coup, and Cost of Living

Myanmar's population has endured two major crises: the COVID-19 pandemic and the military coup. These waves have directly impacted both the public and nuns.

Before the coup, during the first COVID wave, neither the public nor religious practitioners faced exceptional hardship. Donors were plentiful, and government management was systematic, limiting concerns to health issues only.

The COVID wave that hit in June 2020 after the coup was devastating, causing deaths and severe impacts across all sectors. Nunneries' struggles during this period became so severe they made headlines.

Due to health conditions, only healthy adult nuns could go on alms rounds, leaving younger nuns behind. When they did go out, instead of receiving donations, they often encountered "No Visitors Except Relatives" signs.

Unlike during the first COVID period, nuns received no government support or management this time. They survived by rationing their stored supplies, struggling like everyone else.

Even after COVID, the public hasn't recovered. With growing civil unrest and deteriorating economic management, prices have skyrocketed.

Houses that used to say "I pay my respects" now close their doors at the faint sound of "Dana San." Previous donors have reduced their rice donations from two spoons to one, or switched to lower-quality rice. Monetary donations have become almost non-existent.

The small extras once found in alms bowls - onions, potatoes, coffee mix sachets, small monetary offerings - have all disappeared.

Now, a handful of uncooked rice has become the nuns' lifeline.

By Nu Thit Moe (Y3A)

Read More:

Build Myanmar - MediaY3A

Build Myanmar - MediaY3A

Build Myanmar - MediaY3A

Build Myanmar - MediaY3A

Build Myanmar-Media : Insights | Empowering Myanmar Youth, Culture, and Innovation

Build Myanmar-Media Insights brings you in-depth articles that cover the intersection of Myanmar’s rich culture, youth empowerment, and the latest developments in technology and business.

Sign up for Build Myanmar - Media

Myanmar's leading Media Brand focusing on rebuilding Myanmar. We cover emerging tech, youth development and market insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Sign up now to get the latest insights directly to your mailbox from the Myanmar's No.1 Tech and Business media source.

📅 New content every week, featuring stories that connect Myanmar’s heritage with its future.

📰 Explore more:

- Website: https://www.buildmyanmarmedia.com/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/buildmyanmar

- YouTube: https://youtube.com/@buildmyanmarmedia

- Telegram: https://t.me/+6_0G6CLwrwMwZTIx

- Inquiry: info@buildmyanmar.org

#BuildMyanmarNews #DailyNewsMyanmar #MyanmarUpdates #MyanmarNews #BuildMyanmarMedia #Myanmarliterature #myanmararticle #Updates #Insights #Media